Wisconsin Film Festival: Cutting to the chase, and away from it

Thursday | April 13, 2017 open printable version

open printable version

Nocturama (2016).

DB here:

Despite my recent jab at D. W. Griffith, I gladly give him credit for making crosscutting a central technique of narrative cinema. Using editing to switch our attention from one story line to another is a fundamental resource of moviemaking everywhere.

Crosscutting is most apparent in those passages of quickly alternating shots that build tension during chases and last-minute rescues. That’s a prototype of what we credit Griffith with consolidating. But crosscutting is used outside such climactic stretches. Hollywood silent features often crosscut story lines throughout the film, without pressure of a deadline and without much happening in some lines of action. It seems to be a way that filmmakers found to keep the audience aware of many story strands.

Crosscutting is a cinematic version of a very old narrative strategy, that of alternating presentation. Once you have several story lines, you can switch among them. Homer does this in the Odyssey, interweaving Ulysses’ wanderings, Telemachus’ efforts to find him, and Penelope’s holding off the suitors.

Homer initially handles these lines in large blocks, in separate “books.” After attaching us to Telemachus in Books 1-4, Homer shifts us to Ulysses for a long stretch. Such interlacing can be found in medieval narrative too, and of course it dominates modern novels, with chapters shifting among action lines and character viewpoints.

Crosscutting large chunks can give way to shorter bursts. Ulysses’ travels occupy several books, but as he approaches Ithaca, Homer interrupts Book 15 to switch back and forth between him and Telemachus, also headed for home. In cinema, this sort of accelerated crosscutting, often driven by a deadline, has become identified with Griffith’s The Lonely Villa (1909), A Girl and Her Trust (1912), and other Biograph shorts. He lifts the principle of crosscutting to a vast scale in his features. The Birth of a Nation (1915) alternates North and South, home front and battlefront, carpetbaggers and Klansmen in a novelistic fresco.

Crosscutting usually implies some degree of simultaneity. While Telemachus searches for his father, Ulysses leaves Calypso and the suitors run riot in the palace. The notion of actions taking place at more or less the same moment is especially important in chases and last-minute rescues.

As a plot reaches its climax, there can be a sort of site-specific crosscutting too. Once Ulysses and Telemachus have joined forces to slaughter the suitors, Homer’s narration sometimes switches among areas of the fight, as in the battle scenes of the Iliad. While father and son hold off the suitors in the main hall, two servants capture one suitor in a storeroom. We recognize this technique of adjacent alternation when novels and films gather all the major characters in one spot for the climax and shuttles among them.

Crosscutting remains a basic filmmaking tool for most movies on our screens. Where would the Fast and Furious franchise be without it? But some contemporary filmmakers have made fresh uses of the technique. In Inglorious Basterds, Tarantino adopts the big-segment option, alternating lengthy blocks of action before using faster crosscutting when characters converge at the climax. Christopher Nolan has experimented with various tactics, including crosscutting different phases of the same action (Following) and crosscutting among embedded segments, dreams within dreams (Inception).

So there are still lots of options out there to be explored. Just look at some films shown at our Wisconsin Film Festival. Beware, though, of light and heavy spoilers.

Attachment plus anxiety

Frantz (2016).

At one end of the spectrum: Must you always use crosscutting? Wigilia, a charming short feature by Graham Drysdale, suggests not.

It’s built on two Christmas eves a year apart. In the first, a Polish refugee who cleans house for a brusque businessman is alone for the holiday and in his apartment prepares the traditional holiday meal—not for herself but for her absent family. She’s interrupted by the businessman’s vaguely hippy brother, and the two learn about each other as they share the meal. In the second evening, after the businessman has left the apartment to his brother, she returns and they bond more intensely.

Apart from an inserted dream sequence, we stay within the apartment. This concentration derives from the production circumstances; Graham explains that he was given a chance to make the film in short order, and to keep it manageable he came up with the idea of limiting the locale. He shot 53 minutes of footage in five days in the apartment, then did the two final scenes in two days. The narrowly focused drama, with many lines improvised, has no need for the free-roaming tactics we associate with crosscutting.

Crosscutting tends to give us a fairly unrestricted range of knowledge; often we know more than any one character. In The Girl and Her Trust, the telegraph operator holding off the robbers can’t be sure that her boyfriend is rushing to her rescue, and he can’t know how close the robbers are to seizing her. Alternatively, when we’re mostly restricted to one character, we don’t find a great deal of crosscutting.

That’s the case in François Ozon’s Frantz, a remake of Lubitsch’s Broken Lullaby (1932), also shown at WFF. Anna’s fiancé Frantz has been killed in the Great War. Out of sympathy his parents have taken her in and treat her as a daughter. But when she sees Adrien, a melancholy Frenchman, haunting Frantz’s grave, she gets curious. Most of the ensuing film is restricted to what Anna learns,

Adrien visits the family. Flashbacks lead us to think he’s what he hesitantly claims to be: a friend of Frantz from prewar Paris. But he has been pressed to tell the parents what they wished to hear. Adrien actually came to the village to beg their forgiveness for killing Frantz on the battlefield, where they met for the first time. Although we surely have reservations about the sad, apprehensive young man, we don’t learn the truth until Anna does, at about the midpoint of the film’s running time. By this time she has fallen in love with him.

There is some alternation of viewpoint in the film. A few scenes attach us to Adrien during his stay in the village, chiefly when he confronts bitter locals who still consider France their enemy. Still, these scenes don’t give us much direct information about the true backstory. And after Adrien has left and Anna has sought to keep the parents in the dark about the past, we remain attached to her. No crosscutting shows us Adrien’s return to France and his life there. As a result, we’re able to feel curiosity and suspense when Anna decides to track him down. The revelation of his civilian life raises a set of unexpected conflicts.

Both Wigilia and Frantz show that avoiding crosscutting can be a powerful way to keep our attention fastened on characters, the better to let their words and behaviors, as well as their inner lives, get primary emphasis. Crosscutting yields a panorama, while refraining from it can aid portraiture.

Crosscutting as usual

The Student (2016).

More toward the center of the spectrum lies ordinary crosscutting, the alternation among scenes that provide a broad perspective on the action. In Arturo Ripstein’s Western Time to Die (1965), the plot alternates between scenes featuring the returning convict Juan Sayago and episodes showing the reactions of different townsfolk—chiefly the sons of the man he killed. We also learn of efforts from women in the town to prevent the sons from taking revenge. This “moving-spotlight” narration isn’t perfectly omniscient, though. The plot gradually fills in information about what led up to Sayago’s crime, while revealing that the sons’ mission would amount to avenging a dishonorable father.

A similar sequence-by-sequence approach is seen in The Student, aka The Disciple, a Russian film by Kirill Serebrennikov. A fanatical teenager has become the scourge of the classroom, barraging teachers and pupils with Bible quotations and denunciations of bikinis. His mixed-up fundamentalism, which leads him at one point to challenge evolution by donning a gorilla outfit, is unpredictable and a pure power trip, Biblical bullying.

His mother can’t manage him, the administrators are reluctant to take stern action, and the school priest sees him as a potential recruit to the clergy. Only one teacher, Elena, challenges him with a mix of humor and sympathy. But to combat his increasingly wild behaviors, which include making himself a full-size cross which he can stretch out on, she too sinks into Scripture. She hopes to quote the Bible back at him and dislodge his dogmatism, but she too becomes obsessed and estranges herself from her boyfriend. Meanwhile, Venya gets his one true disciple, a limping underdog, and his campaign against homosexuality, science, and secularism turns violent.

A good part of the narration locks us in to Venya’s Dostoyevskian ferocity, thanks to a restless use of the “free camera” in lengthy following shots. (The film has only about 150 shots in 113 minutes.) But we do range more widely to get a broader view. The moving spotlight shows the mother’s frantic consultations with school officials, and Elena’s clashes with them, as well as with her boyfriend. Still, the climactic scene, which assembles all but one of the characters in a single meeting, has no need of a broader view. Like Wigilia, The Student draws its final power from drilling down into a confrontation around a table.

Gaps and folds in time

Killing Ground (2016).

Griffith rang many changes on his last-minute-rescue template, and one of the most startling occurs in Death’s Marathon (1913). A dissolute husband, bored with his life, decides to commit suicide and notifies his wife by phone. She calls the family friend, who races to prevent the death. Surprise: He’s too late.

A hundred-plus years later, crosscutting builds and then deflates suspense in the Romanian film Dogs, by Bogdan Mirica. There are two protagonists: Roman, a city fellow who has inherited his grandfather’s idle farm, and Hogas, the police chief. Both face off against sadistic hoodlum Samir and his thugs. A human foot has popped up (literally, in the first shot), and Hogas tries to trace its owner, while Roman decides how to dispose of the farm. Samir explores other possibilities, none very savory.

At first we’re restricted to Roman, who is frightened by distant lights and gunshots out on the property, and Hogas, who doggedly pursues his investigation. The alternation between them keeps Samir offscreen for some time. When he surfaces in a suspenseful drinking bout with Roman, and when Roman’s girlfriend comes to pay a visit, the threats start building.

The climax starts out as pure Griffith. Mirica crosscuts Roman’s drive back to rescue his girlfriend, Hogas’ pain-ridden walk to the farmhouse, and Samir’s ominous approach to the isolated woman. Interestingly, the pace of the cutting doesn’t much accelerate in these last moments; there isn’t a lot of alternation, and the emphasis is on prolonged actions (Hogas’ trudging pace, interrupted by coughing up blood, and Samir’s laconic dialogue with the girlfriend).

By the time Hogas arrives, he finds he’s too late. The conventional mystery and suspense of the first stretch are undercut by showing us only the eerie aftermath of a violent climax. Art-cinema norms can de-dramatize crosscutting, but the maneuver remain a revision of what Griffith tried for in 1913.

Three years after Death’s Marathon, Griffith showed the possibility of crosscutting radically different time frames. Intolerance (1916) interweaves four historical epochs while using crosscutting within each one as well. Since then, crosscutting has sometimes been used to juxtapose past and present (The Godfather Part II, The Hours), or alternative futures (Sliding Doors), or a real story and a fictional one (Full Frontal). Interestingly, Griffith is a bit more daring than these directors. These films usually alternate sequences or entire blocks. At first Intolerance does that too, using titles to mark the shift among its four eras. But as the film reaches its climax, Griffith cuts freely from one period to another. These shot-to-shot time shifts, jumping centuries in the burst of a cut, remain an audacious formal discovery.

In all these examples, we’re cued to realize when we move to another period. But Killing Ground, a grueling Australian thriller by Damien Power, doesn’t announce its time-shifting. It exploits our default assumption that crosscutting implies more or less simultaneous action.

At first Killing Ground does give us rough simultaneity, alternating between the yuppie couple, Ian and his fiancée-to-be-Sam, and a pair of gun-loving locals. But then the couple make camp near another family’s tent.

Through careful use of eyeline matches and other continuity cues, the narration welds together actions that are actually taking place at different times. The family’s evening meal and their foray into the woods happen well before Ian and Sam arrive, but the cutting implies that the two groups are living side by side.

Like Griffith, at moments Power shifts between the two periods on a shot-by-shot basis. Small disparities, like a baby bonnet and the placement of the campers’ vehicles, accumulate. By the time Ian follows one of the psychopaths into the woods, we realize that earlier events have been salted through the present-time action, the better to delay revealing the family’s fate. From then on, orthodox crosscutting takes over as Ian runs for help and Sam tries to hold the rampaging peckerwoods at bay.

The kids aren’t alright

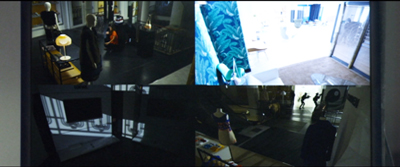

At the distant end of the spectrum, how about building a whole movie out of full-blown crosscutting? A sustained example at WFF was Bertrand Bonello’s Nocturama. (Major spoilers ahead.)

For the first fifty minutes or so, we follow nine young people silently threading their way through Paris. They ride the Métro, pace along the street, pair up, separate, crisscross, and assemble at four sites—a line of parked cars, an office building, a Ministry, a statue of Joan of Arc. They’re setting bombs.

We can identify them only through their looks and behaviors. David and Sarah touch fingers fleetingly on a train. We learn from flashbacks that Samir and Sabrina are sister and brother, and their friend is the younger African Mika, all presumably from emigrant families. Flashbacks also show them meeting to plan their action and, once set on course, dance the night away.

There’s an unexpected shooting, but the bombs go off more or less as planned. The group assembles in an upscale department store to meet another confederate, the security guard Omar who will host them overnight. This brief “nodal” moment of unification melts away. Crosscutting follows them as they wander from floor to floor in a parallel to their passages through Paris.

The first section merges the art cinema’s best friend, the prolonged walk, with a thriller-based suspense: we don’t really know what they’re up to until we see a pistol at around 18 minutes and bomb materials somewhat later. The threads knot when we see a quick montage of the bombs.

This fine-grained crosscutting looks ahead to the fragmentary handling of the action in the department store, where the moving spotlight shifts rapidly as the conspirators disperse, assemble in pairs or trios, and disperse again.

Crosscutting is the principal way filmmakers imply simultaneous action, but a lesser option, often favored by Brian De Palma, is the split screen. Bonello uses this device to show the result of the bombings. The shot looks forward to the quiet surveillance-camera display in the security office as the police prowl the shopping aisles. We see the kids moving from quadrant to quadrant, with an occasional flare marking a nearly soundless kill.

The terrorists’ motives are barely sketched, and they’re a cross-section of middle-class and working-class kids. Some are unemployed, others have low-end jobs, while others are on track for professional careers. A flashback shows several, perhaps meeting for the first time, while waiting for job interviews. The film’s second large part paints them as victims of consumer lust as they try on upscale fashions and make-up, but the point isn’t hammered home. To some extent they’re just killing time in what they think is a safe house.

Nocturama‘s crosscut climax balances, in more condensed form, the first section, as the conspirators are discovered by the police. At one point, an innocent who has come upon them by accident gets more emphasis than the gang members. His final moments are replayed through multiple viewpoints, as if the stranger’s fate drives home to them what death looks like up close. Soon enough each one will know exactly.

It might seem the height of film nerdery to join up films seen at a festival through their different uses of one technique. But is it any more of a strain than those journalistic accounts of how a batch of festival choices reflects The Way We Live Now? Every Berlin or Cannes or Toronto seems to bring forth think pieces looking for a common thread among radically different films, hoping to find today’s social mood in movies begun perhaps years before? Like most zeitgeist readings, they’re pretty easy to whip up.

But technical choices are more concrete than hints of the mood of the moment. Moreover, if you’re interested in cinema as an art, it can be enlightening to reveal the variety of creative options that are still available. The art may not progress, but our understanding of it can. And it’s heartening to find filmmakers refreshing traditional techniques to give us powerful experiences.

Just as important, studying how our contemporaries find new possibilities in something as old as crosscutting can encourage ambitious filmmakers today. The menu is open-ended. There’s always something new, and rewarding, to be done.

We had a wonderful time at this year’s Wisconsin Film Festival. Thanks to all the people and institutions involved, and especially the programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser. Each year it just gets better.

Wigilia is currently streaming on Amazon. Nocturama has just gotten a US distributor, the enterprising Grasshopper Film.

Good discussions of interlaced plotting in medieval tales are William W. Ryding, Structure in Medieval Narrative (Mouton, 1971) and Carol J. Clover, The Medieval Saga (Cornell University Press, 1982). Yes, it’s Carol “Final Girl” Clover.

For Tarantino’s use of block construction and time-bending, go here. We discuss Nolan’s penchant for crosscutting in this entry and that one, and at greater length in our e-book on his work.